CLP Launch Event: Session One

A recap of Abir Kopty's conversations with Nour Abo Aisha, Taqwa Al-Wawi, and Samah Zaqout

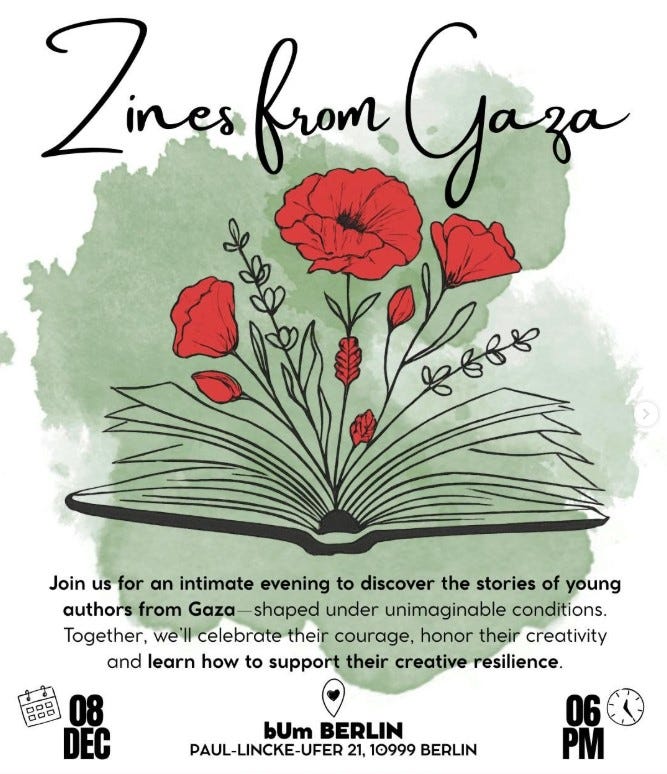

On December 8th, Zines from Gaza joined PALLIES in Berlin for an evening dedicated to amplifying the voices of young authors from Gaza. Through zines, storytelling, and conversation, the event highlighted what it means to create art and literature under the conditions of siege, displacement, and ongoing genocide.

The program included an introduction to the Zines from Gaza initiative, presentations of Gazan authors and their work, as well as live conversations where the authors spoke about their daily realities, the challenges of their creative work, and the power of collective storytelling. Abir Kopty was the event moderator.

Abir is a Palestinian journalist and writer, based in Berlin, and the senior editor and host of Almostajad. She holds an MA in Political Communication from City University, London, and is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Media and Communication Studies, Freie Universität Berlin. She contributes political analysis to media outlets such as Middle East Eye and TRT, and hosted in 2018 “Eib”, an audio podcast about motherhood and parenting produced by Sowt Podcasting.

Abir spoke with Leila Boukarim about Zines from Gaza, prior to introducing the authors.

Leila began by saying, “I want people to hear their stories. I want them to understand what it’s actually like living in this situation, and I want them to wake the hell up. I want people to wake up and to do something about this.”

“What’s next, Leila?”

“Well, we’ve been doing this for three of four months now, and we have 17 published zines, in eight or nine languages, and we have quite a few more in the pipeline, and some of our authors are already working on a next zine, and so we’re very grassroots, purely volunteer driven, which is a beautiful thing, and it really goes to show what is possible, what we can make happen when we come together and all care about the same thing with one objective.

And of course, one thing I failed to mention is that all the money that we make from the sales of the zines go to the individual writers so they get to make money off of their work. So for now, this is what we keep doing, and, I feel this has inspired many. We are over 250 people in the collective now, all around the world, really, truly all around the world, and I hope that more people are inspired by this and more people are moved into action, whether you know, their action looks like this or something completely different.”

In the first session, Abir Kopty interviewed three young writers, whose zines released just a few months ago.

If there is one thing you’d like the audience to know about you that is not on your CV and bio, what would it be?

Taqwa Al-Wawi: “Hi, everyone. I’m happy to be part of this event. Thank you all for joining us. Actually, I want all the people to know that all our words and languages never truly touched the surface of what we have lived through during the genocide. Behind every story, there are layers of pain the world never sees, and I try to convey everything, but sometimes words simply failed.”

Samah Zaqout: “First of all, I want to thank you all for giving me this opportunity to participate in such a great event and to find my voice. I hoped that people would hear our voices for so long and thank God, it’s happening right now. The thing that I want people to know is that we are human, like everyone else and we do have rights, and not only rights, we do have passion and dreams, that really color our days.

For example, I don’t only like writing. I love cooking. I love singing while at home. I love cooking so much. I was the one that people go to when there is a birthday, so I do the dishes and so on, but unfortunately during the war, cooking has become the thing that I hate to do because I spend so much time cooking on fire, just to finish with a plate filled up with canned food, and I’m always worried. I’m always afraid that I will be burned on something because of the fire. Sometimes it catches so wildly, which makes me always afraid. It makes me reach to the point that I don’t like cooking anymore, even when sometimes I want to cook, I just remember these days that I was suffering and struggling when making these dishes.

I also love swimming, but again, the sea in Gaza has become a place that is so dangerous to go to and I feel always that even the air in the sea is now different. I don’t know why. The sewage, the tents, the dust, the rubble that surround this sea of Gaza makes it sometimes unrecognizable. I feel it’s different.

So we do have so many dreams, we do have so many things to do, we do have a passion, we do have talents, we do have rights, we have a family that we cherish. I have five sisters and one brother and the best parents in this world, and I do love them so much, to the extent that I can’t even think that I can leave them. I got some scholarships abroad during the war, but I couldn’t make the decision to leave them. So I want the world to understand this and to treat us as equals because this is what we deserve.”

Nour Abo Aisha: “Something I want to share that isn’t in my CV is that I love life and I love dancing in the theatre. I love cooking. I love life, but you know here in Gaza, they take everything that we love. I lost everything. I lost my favorite comfort zone in Gaza, my room, my place where I grew up. And now I’m just finishing the days like this without making something I love. I’m just wasting my time in Gaza here. I want to practice my favourite hobbies, but I can’t. There’s no tranquility here to allow me to practice the things I love. But I’m still here, speaking to you, even in the street now and the rain behind me in the background. So we are not numbers. I just want all of the people to consider us as a human being with passion, with hobbies, with these emotions. We share the same psychology. I want all the people to hear that we love life, but they just put us in a box, and tell us to adapt to this life, and I don’t want to adapt to this life. I want a live as you.”

Taqwa you wrote in one of your articles, “Writing is not a cure, but a testimony.” Do you think that they can be both, that sometimes testimony can be a cure as well?

“Yes, I do believe writing can be both. Actually, I write because if we don’t document our stories, the world will only hear the Israeli occupation’s narrative, and that’s unacceptable to me. Writing allows me to share our truth and carry the voice of my people to the world.

As Dr. Refaat Al-Areer said, may he rest in peace, “Every person here has a story. And these stories deserve to be told.” So, at the same time, writing is also my form of healing, we can say my therapy, okay, but it drains me emotionally because of everything we carry, but it is essential—not just for me—but also for ensuring our experiences are remembered and understood.”

Taqwa was there a moment where you needed to write in order to heal? Can you share with us one story in which you really felt this writing is going to help me heal?

“I stared to write about everything I lost. When I lost my friends, all of them, I wrote a full article, about this topic. I thought I should write about these things, to document them and to talk to the world about what is happening here. I lost all my friends, and I wanted to make all these names to remind the world that we are human like you, we have friends, but the Israeli occupation stole all these friends from us. So I thought in that moment, I should write this story, to document it.”

Nour, you also wrote “I once dreamed of a vibrant youth, full of achievements, love, flowers, and candlelight. I imagined a phase in life which would have meaning on every level, but the war took everything from me.”

Do you think writing can help you bring back the things taken from you?

I believe writing doesn’t bring back those that I have lost, but it brings back my voice. It’s the only way, I can scream without (inaudible), the only way I can summon moments, full of life, and resist the idea that the war has reduced us to mere numbers. Yes, writing helps me reclaim meaning, even if I cannot reclaim everything. Like I answered in the cover of my zine, I write despite the pain that rips me, because I believe words can survive even when we don’t. I wrote that line is the midst of heavy bombing, at the time when I had lost all hope of surviving, in September 2025. I left my home just one day before it was bombed, and even then, I was writing, because if Dr. Refaat Al-Areer hadn’t written, hadn’t documented his voice, who would remember him these days? May he rest in peace. So the writing, is the only way for us to be remembered in this unfair world. You live when your voice rises and nothing else.

Samah, you also wrote, “In a war that has displaced over 90% of Gaza’s population, belonging is being redrawn.”

Can you share with us Samah, how you think belonging has being redrawn in these days? What is bringing people together and how did the genocide change the sense of belonging?

As Palestinians, belonging for us, was to do things related to our identity—to dress the Palestinian thobe, to dance to Palestinian songs, to eat the Palestinian food, to read Palestinian art. This is about the identity. To wear the keffiyeh. This is about the identity, the culture, and about the heritage of us as Palestinians, but it’s also about the place. We’ve been born here. We’ve been raised here. We’ve been educated here. This is the place that shaped us as people, as human beings. We’ve been taught how to deal with our friends, how to deal with our families. We know the air of our city. The sea of our city. The neighbors of our city. We make friends, so it’s not only about the identity or culture, it’s also about the place.

Now the place is almost erased. The place has turned to rubble. The place is fractured. I think Gaza is now unrecognizable. Like, I can confirm that more than half of Gaza is now unrecognizable. I walk through its streets, and I can’t know where I am. I was lost with my father in one of Gaza’s streets, and we were just walking and asking people where we are, just to go to our destination and we don’t know how to go, and that place was one of the most famous places in Gaza. We know it very well before the war. So the war turned everything upside down. It erased this.

So we still belong to the culture, we still belong to the heritage, we still belong to Palestine and Gaza, but we don’t feel that we can belong to this destruction, we are not willing to belong to this destruction, to belong to this dust. We don’t belong to this rubble, and to this place, which only carries the pain, and the sorrow, and the agony of people who have been suffering for almost two years and are still suffering.

And we do fight to feel that we belong to this, like even when Gaza is destroyed, even when it’s only rubble, even when it’s only dust and sewage, we still want to belong to this place that shaped us, that raised us, not because it’s now so changed, that we don’t want to belong to it anymore. No, we’re not like this. We still struggle and do our best to belong to this destruction and still can’t know how to belong to this destruction, and this is what I mean that the genocide has changed everything. It has redrawn this feeling of belonging to this place.

I do believe we are still rooted to this land, but we are lost. We are lost in our city. We are lost in the place that raised us. And this is again, the vicious circle that we’ve been living in for so long.

The authors answered a final question about what it means to write under siege and genocide. They recounted the worst things they suffered during the genocide, spoke of the difficulties of making decisions and having a voice while surviving these realities, and expressed frustration with the world’s indifference to the suffering of people in Gaza.

The session closed with the authors reading poems from their zines and answering questions from the audience.

Stay tuned for a recap of Session Two, featuring authors Shahd Alnaami, Mariam Khateeb, and Ahmad Elkhuwaja. We also look forward to sharing a recording of this event.

To be continued…